A New Act

An historic opera house renovation will bring new economic opportunities to Staples.

By Lisa Meyers McClintick

Eighteen years ago, Colleen Frost was facing cancer, grueling chemo and a divorce. She desperately needed something to pull her forward.

“I was told I had a year to live and a 10 percent chance of living longer,” Frost said.

Frost’s twin brother, Chris Frost, knew she had always wanted an extreme makeover home. So it felt like providence when he found a one-block building in downtown Staples with a hidden architectural gem: The 1907 Batcher Block Opera House, which was shuttered half a century ago. It quietly sat like a time capsule waiting to be reopened.

Arts and Economy

Local supporters are hoping state lawmakers will include the Batcher Block Opera House among its bonding projects to cover half of the projected restoration costs—roughly $8.5 million. That would allow the city to buy the building from Frost and begin restoration, which would include fixing the leaking roof, removing mold from walls, modernizing the electrical work, restoring the original Bavarian frescos and murals, installing a commercial kitchen for catering and cooking classes and creating accommodations for visiting performers and artists. The opera house takes up about 5,000 square feet of the Batcher building’s second and third floors and can seat about 750 people with the main floor, two private boxes and a balcony.

McClure Engineering prepared a business plan for Staples and the Batcher Block restoration project while the University of Minnesota Extension Service—supported by Initiative Foundation and local community foundation grant funding—looked at the broader economic impact. It’s estimated the renovation phase alone could generate more than $15 million in regional spending, with about $5 million of that going toward 110 jobs. Once completed, retail space and special events are expected to generate $1.7 million a year. The building also could employ four to five full-time employees, up to 20 part-time staff and draw 4,460 visitors who are expected to spend $540,900 annually.

Having a cultural attraction may make it easier for existing local employers, including Lakewood Health Systems, Trident Seafoods, Central Lakes College and 3M, to recruit employees. “It’s a quality-of-life factor,” Radermacher said. “The arts and the economy go hand in hand. It also connects people in the community.” The building could draw additional businesses, such as a brewery, boutiques and restaurants.

While the glory days of train travel are long gone, Amtrak’s Empire Builder passenger route has been growing with an estimated 139,091 passengers using Minnesota’s six stations each year. About 6,000 of them are dropped off at the Staples Depot, now owned by the Staples Historical Society and home to the Staples-Motley Area Chamber of Commerce. Frost says about 10,600 cars go by a day on U.S. Highway 10.

If local organizers can get the opera house humming again, “the city hopes to draw from a wide radius that includes St. Cloud, the Brainerd Lakes area and seasonal residents and vacationers.”

Without a renovation, however, the building could be lost. But Frost and local organizers are optimistic they will get the lights back on and that once again music will lift its way up to the balcony.

“It needs to be done, or [the opera house] will end up disappearing,” Radermacher said. “I think everyone is ecstatic we’re moving forward.”

“A new dream happened,” Frost said of her decision to buy the opera house in 2003. She and her brother credit their work to give the opera house new life with helping to save hers. She remembers clearing the space out in those early years and happily “laying on the floor and looking up at the monkey faces, lion’s heads, and dragons, and cabbage roses [in the Bavarian fresco work], and listening to my brother playing a baby grand.”

The siblings dreamed big and worked hard to get the Batcher Block Opera House building on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. They brought in actor Mickey Rooney, musician Lamont Cranston and comedian Louie Anderson to perform and enjoy the theater’s stellar acoustics. They held dozens of other events to build enthusiasm and fundraising momentum.

The project lost steam as the 2008 Recession hit and Frost diverted energy to helping local leaders successfully save the 1909 Northern Pacific Railway Depot, which is a short stroll from the Batcher Block opera house. Armed with a recent business plan, community leaders and a steering committee are now looking at reviving the Opera House and its building as a regional arts hub and cultural centerpiece.

“From what I understand, it’s one of 13 [opera houses] in the nation with the original artwork and structure,” said Melissa Radermacher, Staples economic development director. “When I walked in there, I got goosebumps. . . . You literally feel like you stepped back 100 years.”

A $5,000 grant from the Initiative Foundation, and a $2,500 grant from the Staples-Motley Area Community Foundation, helped to fund an economic impact study. The final report showed that a $17 million renovation could spark an economic and cultural renaissance that could have a positive ripple effect that extends beyond this city of almost 3,000 residents.

Glory Days

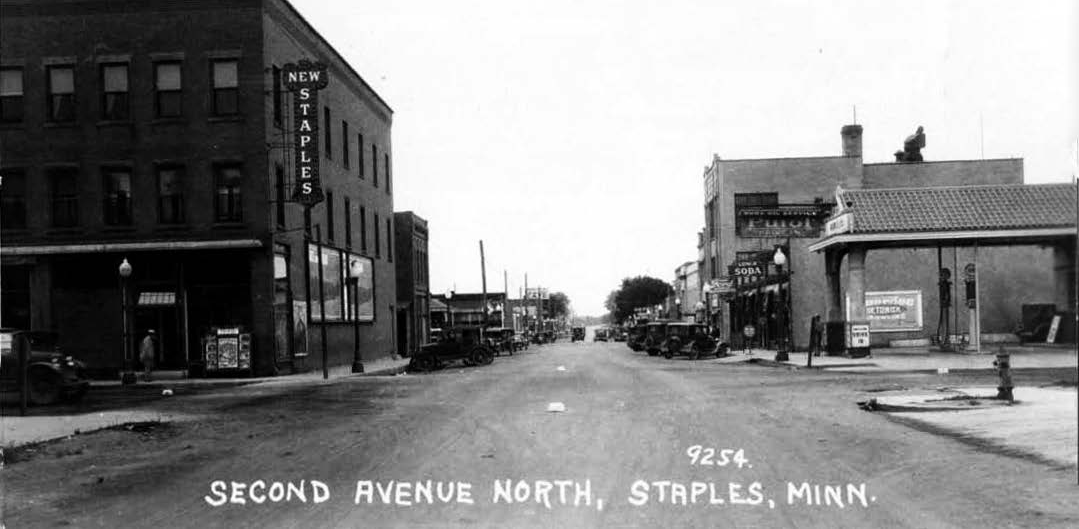

At the time the Batcher Block Opera House was built, it was one of several opera houses in Staples, which was a hub for train travelers. Up to 25,000 passengers a day stopped in this Central Minnesota town and needed to find something to do while their trains were rerouted or rearranged at the switchyard.

Charles Batcher, who built many of Staples’ homes, held off finishing his opera house until he could add electricity and get water pumped to the upper levels. When completed, it was considered the nicest opera house in town. The original chairs still have hooks for top hats.

“Cities in that era would show their sophistication by having performance centers,” explained Don Hickman, vice president for community and workforce development at the Initiative Foundation.

The theater weathered the transition from opera and vaudeville to silent pictures and movies. It was used for roller skating during the 1930s Depression before being shuttered. The upper level of the building eventually was turned into apartments, and many renters who lived there never knew about the locked-up opera house down the hall.