Cooking Up New Solutions

Hilltop Regional Kitchen provides as many as 100,000 meals a year to senior citizens in Central Minnesota.

By John Reinan | Photography by John Linn

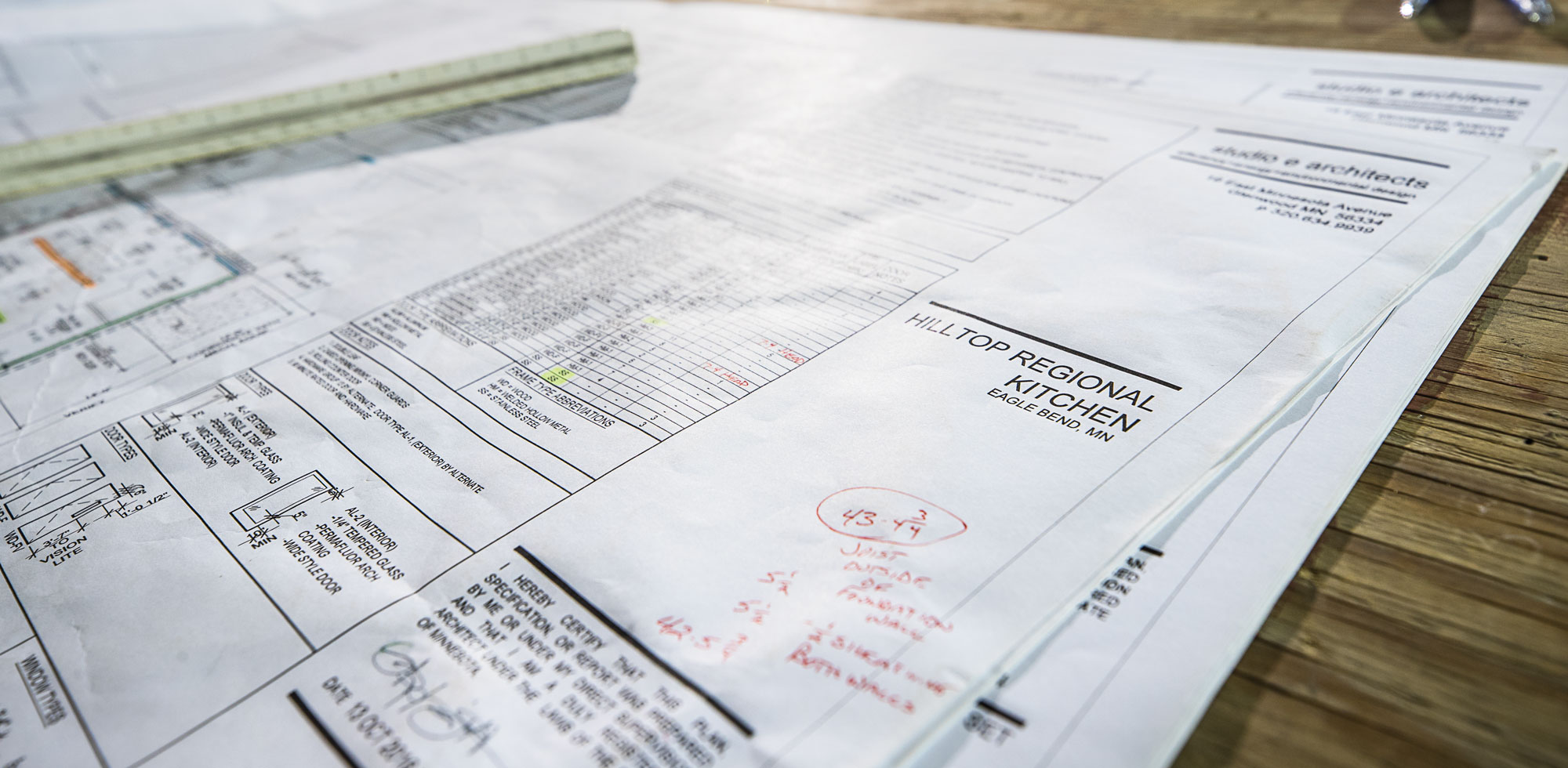

In the Todd County town of Eagle Bend, an abandoned high school is getting a new life as a regional kitchen that will prepare as many as 100,000 meals a year for the area’s elderly and disabled residents.

Hilltop Regional Kitchen, funded by an array of private and public grants, along with contributions from citizens and civic groups, is set to open this summer in the renovated Eagle Bend High School, which closed several years ago.

Replacing the current cramped facility at the Eagle Bend Senior Center—located in a 107-year-old former drugstore building—the new regional kitchen will meet commercial standards and more than double the capacity of a service that provides individual Meals on Wheels as well as supplies of packaged frozen meals to senior citizens throughout Todd and Wadena counties. Across Minnesota, 21 percent of the population will be 65 or older by 2030, according to data from Minnesota Compass. The ratio is notably higher for the same period in Todd and Wadena counties, where nearly 27 percent of the population will be 65-plus.

That makes now the right time for Hilltop Regional Kitchen to grow as the demand for meals skyrockets, said Rick Hest, president of the Eagle Bend Senior Center.

“We went from under 30,000 meals a year five years ago to over 50,000 now,” Hest said. “We don’t have enough storage for all the supplies that come in to make these meals.

I don’t know how the volunteers are doing it in our current kitchen. They’re crawling all over each other like ants!” After the kitchen staff prepares hundreds of individual hot meals each day, drivers head out to deliver them throughout the two counties. The kitchen is one of only two facilities in the state that also prepares “bundled” meals, which are 14-day supplies of frozen individual meals that the recipients can heat up. Among the towns the new kitchen will serve are Wadena, Verndale, Browerville, Long Prairie, Staples, Clarissa and Motley.

The total cost of the regional kitchen is expected to be $850,000 to $900,000, and that could climb a bit if additional money can be raised for a few hoped-for amenities, such as a new parking lot.

The Initiative Foundation helped move the project ahead with a pair of critical $10,000 grants. One funded early planning and was the first grant the effort received. The second paid for a feasibility study that recommended the closed high school as the site of the new regional kitchen.

“We helped get the wheels turning early in the process,” said Dan Frank, the Foundation’s senior program manager for community development, speaking not only of this project but of the Initiative Foundation’s work in general, which includes serving as a resource, sounding board and cheerleader for citizen-led community efforts.

The Needs of Elders

Underpinning the nutrition effort is a stark demographic fact: Rural Minnesota is quickly growing older.

About one in every seven Minnesotans—more than 800,000 people—lives in a rural area or a town of less than 10,000. These rural residents are twice as likely to be at least 80 years old when compared to their counterparts in the state’s urban areas, according to a recent report by the Minnesota State Demographic Center.

Many of these older adults live alone, and they often lack mobility. Hoping to remain in their homes, they often need help with some elements of daily living, including proper nourishment.

That’s the goal of meal programs like the ones provided by the Hilltop Regional Kitchen. Money spent on these programs is returned many times over in savings elsewhere, particularly in healthcare costs, said Julie Myhre, director of the Office of Statewide Health Improvement Initiatives in the Minnesota Department of Health.

“For every $1 of federal Meals on Wheels spending, there is a $50 return on Medicaid savings alone,” she said. For its part, the state sends more than $17 million a year to community health boards to promote access to healthy food and physical activity, and to discourage tobacco use.

“It’s about changing the environment, the systems people are a part of,” Myhre said. “We provide guidance on evidence-based strategies, but these efforts are locally driven. Communities choose what strategies make sense for them.”

Teresa Ambroz, a state nutrition coordinator, said meal programs are an important way to increase access to healthy food for Minnesota’s rural seniors. “In rural areas, the grocery stores are often closing,” she said. “That was the case with this group in Todd and Wadena counties. Also, as you age, your ability to get out is reduced, and the transportation systems are not there in the rural areas.”

Verna Toenyan, Todd County’s aging coordinator, has seen that scenario play out repeatedly.

“We have a ton of people who frequent the dollar stores [to buy food], and they’re not getting their fruits and vegetables,” she said. And many of the rural elderly are living on a thin financial edge.

“If you have an illness or some kind of an issue with your home or your vehicle, then your funds go for that, and you’re sitting there eating maybe one meal a day—or no meals,” Toenyan said. “It’s not just the poor any more who need help. The high cost of medication and the fact that people live a lot longer means that middle-income people are more affected than they used to be.”

A Larger Community

That’s why the meal program is so essential, said Hest, the senior center president. “I do volunteer taxes, and I know what some of these people are living on,” he said. “Holy moley, some of these people live on very little.”

The Hilltop Kitchen could serve as a model for similar programs throughout Minnesota, said Loren Colman, the Department of Health’s assistant commissioner for continuing care for older adults. The department assisted the Hilltop project with a six-figure grant.

“You can’t have a kitchen doing this in every single community,” Colman said. “We liked this project because it was regional in nature. They looked at their area and said, ‘How can we use this as a hub and spoke?’ That’s a model that we really think is valuable in the less populated areas of Minnesota.”

The economies of scale make a big difference in food purchasing and preparation, Toenyan said, and the burden on volunteers is less.

“It takes a whole lot of volunteer commitment by the communities that have a kitchen or a senior center,” she said.

“It’s easier to staff a regional kitchen than multiple smaller ones.

“Once we develop this format, they can take this template and have a kitchen design that can work anywhere,” she said. “It’s exciting. We could never have done this without the help of the Initiative Foundation. I’m very grateful to them.”

The kitchen and its meal program provide more than food for the body. They also help nourish the soul, Myhre said.

“Mental and emotional health is a key component of overall health,” she said. “In Todd County, there is a higher percentage of seniors living alone. These home-delivered meals sometimes offer the only opportunity for them to connect with people.”

Added Hest: “These volunteers do more than just deliver food. I’ve changed innumerable light bulbs; I’ve dropped things off at the library.”

Across Minnesota, communities are slowly embracing cooperation, according to Frank.

“We need to get away from that Friday-night-lights football mentality … that notion that we played that other city in football, so we’re not going to cooperate with them,” he said.

“We understand that cities have different neighborhoods. And I think that counties would do well to realize that most people live and operate in more than one limited geographic area.

“The more we can look across those boundaries and see ourselves as one larger community, the more we’ll see opportunities for efficiency.”