Disconnected

Loneliness and social isolation are taking a toll on society. What can we do to reverse course?

By Betsy Johnson | Illustration by Chris McAllister

Something in our everyday lives puts us at a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death. You might think it’s something familiar, like smoking or stress. In fact, it’s social isolation.

But how in the world can we feel isolated? We are connected to people all over the world all the time, especially through social media and other digital technologies. Digital technology is not inherently good or bad, but it is powerful—and influential. It can provide us with instant information—traffic, weather, news, pop culture—and deliver the healthcare information we seek with the tap of an app or a few keystrokes. It can pull us together by breaking down barriers, creating a rich exchange of ideas and connecting us all. It can also push us apart, leaving us unmoored from the truth, awash in anxiety-fueling content and adrift in an ocean of misinformation, disinformation and confirmation bias. More than that, it can erode community cohesion and leave many of us feeling isolated and alone.

Experts say it’s a problem more serious than we might realize.

The Hidden Costs of Social Isolation

In a May 2023 letter called “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy stated that one in two American adults reported experiencing loneliness. “The mortality impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day, and even greater than that associated with obesity and physical inactivity,” Murthy wrote.

Dr. Steven M. Hoover, a retired St. Cloud State University professor of counseling and educational psychology, is working to reduce social isolation and loneliness among seniors. As the Healthy Aging Coordinator for the Central Minnesota Council on Aging, Hoover cites a pre-pandemic AARP study which found that the negative effects of social isolation in the United States cost Medicare $6.7 billion annually.

The AARP findings are augmented by a pre-pandemic report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), which found that more than one-third of adults aged 45 and older feel lonely, and nearly one-fourth of adults aged 65 and older are considered to be socially isolated.

Older adults are at increased risk for loneliness and social isolation, Hoover said, because they are more likely to face factors such as living alone, the loss of family or friends, chronic illness, and hearing loss. Isolation and loneliness can also lead to other issues such as depression and anxiety—across all generations. “The lower the number of contacts, the more likely the person is to be considered socially isolated.”

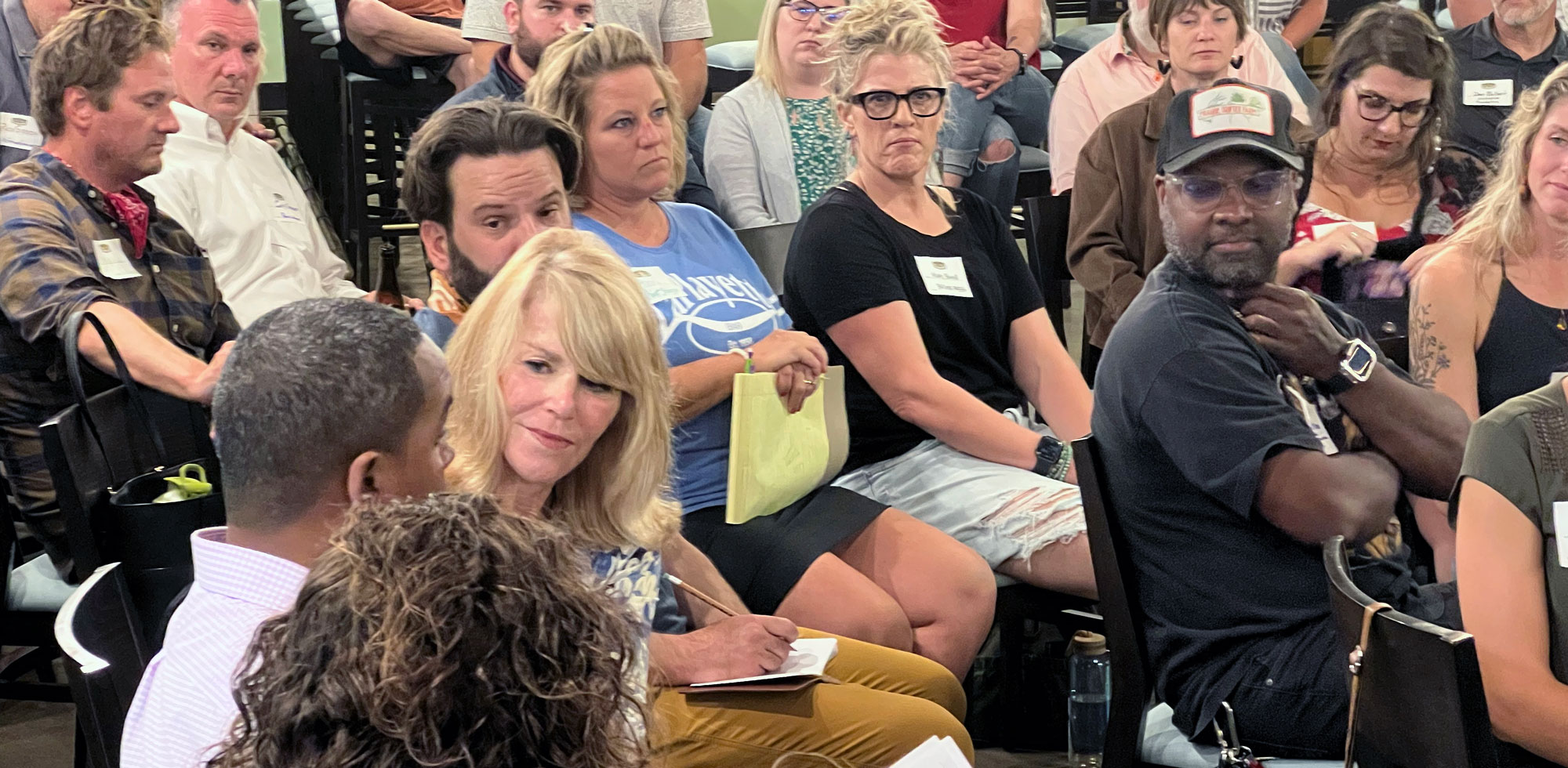

The Initiative Foundation ramped up its efforts to address social isolation and loneliness in early October when it sponsored a Rural Voice town hall conversation in Little Falls. Moderator Kerri Miller of Minnesota Public Radio led a capacity-crowd conversation at the A.T. Black & White to explore barriers to mental health care in rural settings and ways in which we can come together to alleviate isolation and loneliness.

The Foundation will continue its focus in 2024 with a special $100,000 grant round. (Learn more.)

“We want these grants to create good, to restore trust, to deepen relationships, especially with those who are so very different from ourselves,” says Don Hickman, interim co-president and vice president for community and workforce development at the Initiative Foundation. “We’re looking to support innovative ideas that address the unique challenges we face—particularly in rural areas—to bring people together across all spectrums and ideologies. If we can do that, this might be one of the best grant rounds we’ve ever awarded.”

A Case for Real Social Interaction

Carol Bruess, an interpersonal communications expert and author, said social media and the use of digital technology has, in many cases, become a substitute for face-to-face interaction. “The research is clear: The reward centers in our brains get stimulated when we engage in social media. The likes, hearts, retweets and shares of social media literally give our brains a little happy hit. It becomes a feedback loop, keeping us coming back for more.”

Bruess moved to the region in 2022 when her husband, Brian Bruess, became president at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University. She cites the work of Sherry Turkle and her books “Alone Together” and “Reclaiming Conversation,” both of which explore how people confuse the promise of online connection with what we really crave: real and meaningful interaction.

“One of our most basic human needs is relationships, and relationships are built in face-to-face conversation,” Bruess said. “We all need to practice and be in the messiness of real-time relationships.”

Busy But Buffered

It’s no small wonder our social circles are shrinking and that we’re growing more isolated. We can do our banking and satisfy all our shopping needs—groceries, clothing, essentials, hobby supplies and more—without a single human interaction. And if we need a cup of sugar or a tool for a yard project, there’s no need to reach out to a friend or neighbor to borrow what we need. We can simply have it delivered to our door, or we can dash off to the store, run through self-checkout and bustle back home. It’s frictionless and interaction-free, with no greetings, no eye contact, no smiles, no comments about the weather, and no common courtesies exchanged.

According to a 2003–2020 American Time Use Survey, social isolation increased an average of 24 hours a month over two decades. The study found that we spent an average of 142 hours of alone time per month in 2003. That figure jumped to 166.5 hours per month in 2020—an increase of nearly 17 percent. At the same time, social engagement with family, friends, and others—roommates, neighbors, acquaintances, coworkers, etc.—decreased by two-thirds, from 30 hours a month in 2003 to 10 hours per month in 2020.

Add in the very real isolation experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and you have the makings of a loneliness and social isolation epidemic.

Dwindling Connections

In “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital,” published in 2000, author and political scientist Robert Putnam warned that our stock of social capital—the very fabric of our connections with each other—had plummeted since 1950, largely due to generational succession, television, urban sprawl and the increasing pressures of time and money. And that was before the full emergence of the internet and ubiquitous mobile phones with far-reaching data plans crept in to influence our lives.

Putnam’s now-classic book explored the political, religious, and civic lives of Americans and found a decline across most sectors:

Political engagement: While 62.8 percent of the voting-age population turned out to vote in the 1960 presidential election, only 48.9 percent had done so in 1996. Voting saw a resurgence in 2020, with 68.2 percent of the voting-age population casting their ballots. Experts say the jump was fueled by the nation’s fractious political campaigns and facilitated by pandemic-related changes to state election rules.

Religious engagement: The portion of Americans who said they ascribed to “no religion” in 1967 was just 2 percent. By 1990, that number had jumped to 11 percent. Today, there are so many religiously unaffiliated people that social scientists have coined a name for them: religious “nones.” A 2021 Pew Research report found that nearly one-third of Americans identified as “nones.”

Civic engagement: Putnam noted that civic engagement—involvement in associations that share a common goal, such as service, political, work-related, or entertainment-based groups—has dwindled since the 1950s. His research found that communities with high levels of civic engagement tend to be more successful when dealing with problems such as poverty, unemployment, education, crime, and health.

“People who are engaged tend to be more invested in the health and well-being of their communities,” Hickman said. “When people volunteer their time, skills, knowledge and enthusiasm to promote the quality of their community, they’re contributing to the common good. They see their role in a larger context, beyond only what affects them and their families to what affects society as a whole.”

Creating Connection

Bridging differences is at the heart of Nora Hertel’s Shades of Purple project. A member of the Foundation’s 2022-2023 Initiators Fellowship cohort, Hertel’s Shades of Purple is a dialogue series meant to spur community engagement, model civil discourse, and amplify moderate voices. “Bringing people together for substantial and personal conversations does something else—it builds connections,” said Hertel, who launched Project Optimist, an online, solutions-based nonprofit news site with a focus on Central Minnesota. “It encourages speaking from the heart and deep listening.”

In the crush of noise pushing into our daily lives—fueled by a 24-hour news cycle with an ala carte selection of information sources—the sense of having a voice and being heard often gets squelched. The Shades of Purple model, Hertel said, provides a real-time, in-person “opportunity to share our truths and the stories behind them–without interruption.” It’s a simple, mindful practice that Hertel believes can help us come together and feel part of a community.

Research shows that we “are collectively looking at our digital devices eight billion times a day,” Bruess said. If we are looking at our devices, we are not looking in the eyes of another person.

“Empathy has decreased 40 percent in the past two decades, and some argue it is, in part, because we simply aren’t seeing each other.”

She suggests creating spaces where we do not allow technology to be present: at the kitchen table, in the car, in the bedroom, and at meetings. We can choose to leave our devices at home, in a purse or pocket or backpack. “In those moments, we can intentionally and mindfully choose to reflect. Be present. Perhaps even—crazy, I know!—strike up a conversation with a stranger.”

START ENGAGING

- Start a conversation. Talk to people who you already have connections with and build upon that relationship or take an opportunity to authentically get to know your neighbors and co-workers that you just wave at or say hi to in passing.

- Join a club or enroll in a class that intrigues you. You’ll know the people who will be there already share a common interest with you. If you end up not meeting anyone new, you will still get to do something that you enjoy.

- Get involved in your community by attending events and doing things that you have not tried before.

- Explore opportunities to serve and help others within your community. Many organizations offer volunteer opportunities that can give you the chance to contribute to something that you find important.

- Create a larger and more diverse social network. Having a variety of relationships will allow you to gather additional resources, information and opportunities.

- Don’t let technology distract you from engaging with others. Pay attention to ways it may make you feel worse about yourself or others. Use technology as a tool to make positive and intentional connections.

SPECIAL GRANT ROUND: Loneliness & Social Isolation

In early 2024, the Initiative Foundation will launch a special $100,000 grant round to fund projects, programs and community- building ideas that bridge differences and bring people together to alleviate loneliness and social isolation.

WHAT’S YOUR BIG IDEA FOR CENTRAL MINNESOTA?

Grants can be awarded to 501(c)(3) organizations such as nonprofits, schools and local units of government. If you have an idea but lack the right community connection, share it in a Zoom video. We’ll do what we can to match you to an eligible partner in your community. Grant awards will generally range from $5,000 to $10,000.

Visit ifound.org/grants/loneliness-social-isolation to share your idea.